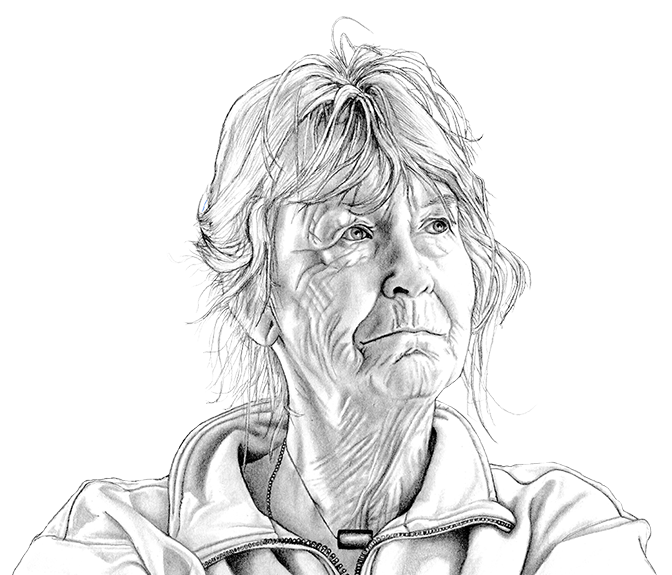

The blinds are always closed in Quita Longmore’s house in the centre of Ladysmith, BC. The covered windows diffuse sunlight and allow her to comfortably move around her house, which has been challenging since she was diagnosed with macular degeneration, which is slowly degrading her vision.

“I’ve always been independent. I’m accustomed to that, and I don’t want to even think about not being independent,” she said.

Longmore was brought up to be self-sufficient. Her father raised her the same way he raised his sons, teaching her how to change a fuse box and use a screwdriver. At 4’10½” tall, Longmore’s mother also had a can-do attitude. A swimming accident left Longmore’s mother quadriplegic, but she learned how to paint once more and walk with crutches even though doctors told her she never would.

Longmore says her mother’s independent spirit and her father’s practicality influenced her adult life — she thought for herself. Longmore’s cousin was diagnosed with AIDS at the height of the epidemic, so she began volunteering with an organization that supported people living with HIV/AIDS. Longmore regularly visited the federal and provincial prisons to connect HIV-positive inmates to resources. Her volunteerism, which spanned from 1986-2004, led to her being awarded the Governor General’s Caring Canadian Award.

At the age of 79, Longmore is determined to live out the rest of her days in her own home – not in a nursing home. She is not alone. A 2020 poll commissioned by the Canadian Medical Association found 85 per cent of Canadians will do “everything they can to avoid” going into long-term care, and a 2021 Angus Reid survey shows 44 per cent of Canadians “dread” the thought of living in or placing a loved one into long-term care.

“As I get older, I will do everything I can to avoid going into a long-term care home.”

This chart shows agreement with the statement above by age group. From an Ipsos poll of 2,005 Canadians conducted for the Canadian Medical Association.

The COVID-19 crisis has heightened those concerns. In British Columbia, residents of long-term care were 32 times more likely to die from the virus than the general population. Combine the grim statistics of nursing home deaths with a quickly aging Canadian population, and the high cost of long-term care, and the challenges of care for Canada’s elderly population becomes clear.

Dr. Jane Philpott, the first physician to serve as Minister of Health, has been struggling with these issues in both her professional and political work, and has been a leading advocate for Canadian seniors to age at home. The problem, she said, is that, “the federal government has lacked the tools to be able to say: ‘we would like to see more access to home care.’”

“I’m a huge fan of the Canada Health Act,” she said, but explained that it was passed a half century ago, “at a time where most care was delivered by doctors and most care was delivered in hospitals. Fast forward to now, care is often best delivered by non-physicians and more affordably delivered by non-physicians.”

Since healthcare is administered at the provincial level, the best Ottawa can do is offer financial incentives to support and encourage homecare. That’s why, before she left office in 2017, Minister Philpott allocated $6 billion to expand access to home care for seniors, as well as home-based palliative care and community-based care.

The Ministry of Health would not grant us an interview to explain how that investment has paid off, but provided a statement saying, “The federal government continues to work in collaboration with provinces and territories to ensure seniors get the care they deserve, including fostering aging at home.” They went on to write that Canada wants to align with the recommendations of the United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021-2030) by “[promoting] seniors’ physical and mental health to enable them to live longer at home.” Furthermore, in the 2021 budget, the federal government allocated $90 million to launch the Age Well at Home initiative, which provides support for vulnerable seniors to age at home, by matching them with volunteers who help with daily living tasks.

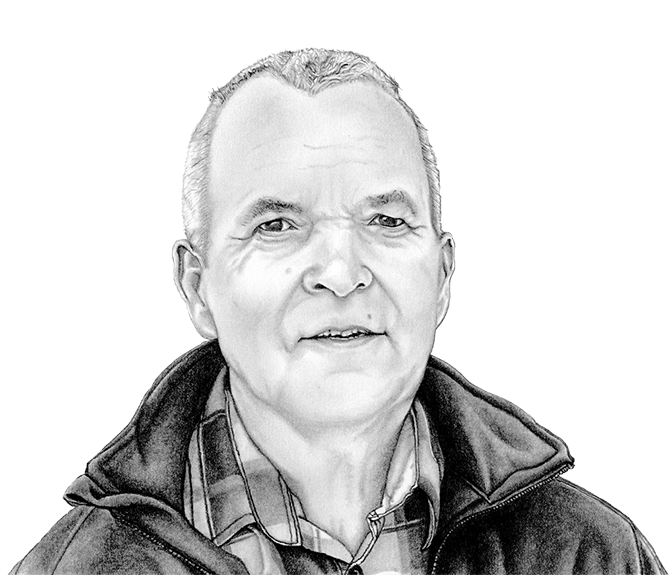

Longmore is fortunate to not have to rely on strangers for her care, since her son Darrell has moved in to help. “I came home for a visit and that’s when I realized pretty quickly that she was going to need some help,” he said.

During his visit, he noticed his mother was struggling to see and was unable to differentiate between characters on TV moving from one scene to the next. She had to give up her driver’s license after almost 60 years on the road.

That prompted Darrell to abruptly quit his job in Texas, find remote work and move back to Ladysmith, where he hadn’t lived since he was 18.

“If I didn’t have Darrell home… I think I would seriously have to start thinking about what I was going to do,” Longmore said. “That’s been the worst thing, knowing that I’m not as capable of fending for myself, by myself, as I’ve always been able to do.”

When it comes to decisions about home versus long-term care, it often comes down to money, particularly as Canada’s population ages.

Canada’s population, 2021 and 2060 projected

In the coming 40 years, the projected number of people aged 60 and above in Canada will increase dramatically.

Population:

“With the aging population… it’s pretty hard to avoid substantial increases in the cost of healthcare for seniors,” said Matt Stewart, who co-authored a series of reports for the Canadian Medical Association and Deloitte on the needs of Canada’s seniors. One of his study’s most dramatic findings was that Canada’s hospitals are filled with seniors who do not need to be there, but have nowhere else to go. Eleven percent of seniors currently in hospital beds could be discharged if home-care could be arranged, but they either do not have the equipment, accessibility or support to transition home.

Canada’s percentage change in population by age group, 2021 and 2060 projected

Statistics Canada projects that between 2021 and 2060, the population will increase by 44.53 per cent. For those aged 70 and older, the projected increase is 112.9 per cent.

“A lot of people are depending on friends and family for basic home care… because they can’t get enough public care,” said Stewart. But survey data shows that many of these seniors would prefer a more formal, government-administered system of home care, which Stewart said is lacking due to factors like shortage of healthcare workers, homecare budgets and administrative burdens.

While home-care is a better option for government budgets, when it comes to out-of-pocket costs for seniors, it is often a different story. A low income senior in B.C., for instance, may pay a similar amount for long-term care and home care. In 2022, the monthly payment of long-term care in the province is between $1,237.20 and $3,575.50, depending on income. Considering the cost of housing and other living expenses in much of British Columbia, a nursing home might be a cheaper option for some seniors.

Demand for long-term and at home care in Canada, plus costs, to 2031

This data from a Deloitte report estimates the increasing demand for care between 2019 and 2031, as well as the combined cost of providing it. The report findings suggest that patients prefer to remain at home over long-term care — a trend reflected in these projections.

Understanding the complex senior care system can be challenging too – knowing whom to contact to arrange homecare, learning what homecare services are available, and even determining what financial support exists for caregivers. For instance, the Canada Caregiver Credit and Employment Insurance offer benefits to people caring for seniors in need of support, but Longmore’s son said he had never even heard of this option. Challenges in navigating the system is a key reason why one in nine new long-term care residents in Canada potentially could have remained at home with proper support.

Still, Canada has developed alternatives to long-term care. These allow seniors to remain independent by staying out of long-term care facilities and supporting each other. Examples include the Canada HomeShare program, which offers reduced rent to young adults who provide companionship and assistance to older adults, and naturally occurring retirement communities where older adults move to apartments, condos and co-ops to remain independent after retirement.

Alternative living arrangements such as the Canada HomeShare program are emerging for seniors, but haven’t expanded to smaller communities such as Ladysmith. For the time being, Darrell and Longmore continue to look after each other for support.

“How do I see myself fitting into her future?” he asked. “Well, I mean, I think, the future is here.”