It’s 4 a.m. in Seoul and Yeong-Im Jung is waiting outside the collection depot. When it opens in two hours, she is among the first in line to unload her cart, piled high with cardboard, plastic, aluminum cans and even an old vacuum cleaner. After weighing her haul, she collects her money and heads back out into the morning streets to continue her work day.

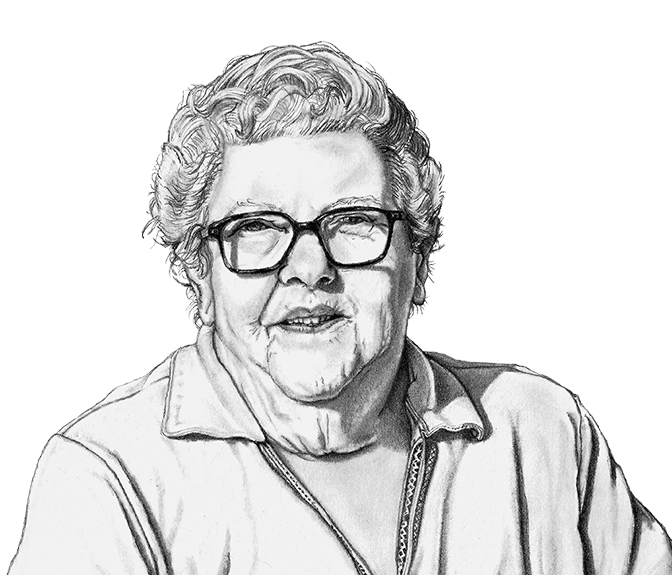

At age 75, Jung is a “pyeji sugeo noin,” which, in Korean, loosely translates to ‘a senior who collects cardboard and other recyclable goods in exchange for small sums of cash.’ There are an estimated two million people in South Korea — most of them seniors — who make their living in the informal trade of waste and recyclables for cash.

Seeing seniors like Jung toiling away in streets and depots may be an unexpected image in a country that historically revered and cared for the elderly. “Hyodo,” the term for filial piety, is grounded in Confucianism, and puts responsibility on children to care for their parents, particularly in old age. But a variety of factors – including increased lifespans, a weak pension system and economic challenges – have conspired to lead to another startling fact: nearly half of South Koreans over the age of 65 today are living in poverty.

South Korea’s income poverty rates (measured as percentage of group)

South Korea’s poverty rate among those aged 66 and older (43.4 per cent) is significantly higher than its poverty rate overall (16.7 per cent). Among those aged 76 and older, this rate climbs to 55.1.

Many poor Korean seniors, like Jung, take on informal, low-paying work, often done under unsafe working conditions, just to meet their basic needs.

She earns about 20,000–30,000 won ($20–$35 CAD) a day collecting waste. Much of the income her family does bring in, she says, goes to care for her 85 year-old husband, who has dementia. Because she never attended school, she has limited options for work. “My work is my life,” said Jung.

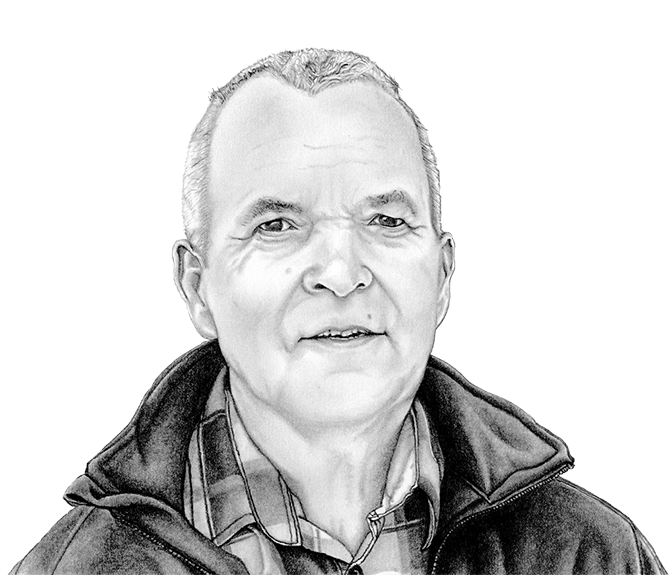

Statistics from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development – the OECD – show Jung represents a clear trend in her country. Among this group of most of the world’s wealthiest countries, South Korea stands out with 69 per cent of seniors over the age of 65 working in some form of temporary or informal employment – five times the average within the OECD. South Korea may have the tenth largest economy in the world, but it is one of the only countries in the OECD in which the risk of poverty increases in old age.

Labour force participation rate of people in South Korea age 65+ compared to select countries

Among OECD nations, South Korea has the highest elderly labour force participation (LFP) rate. (LFP includes those who are employed and those who are looking for work.) Among people 75+, South Korea’s LFP is 23.15 per cent—nearly triple the OECD average of 8.28.

A recent prominent study on aging in Korea found there are a number of factors that contribute to South Korea’s high elder poverty rate – from increasing life expectancy to antiquated employment systems to insufficient pensions.

“[O]n an individual level, there is not enough preparation for retirement,” the study concluded, explaining that high spending on education for their children, combined with high debt, contribute to seniors failing to save enough for retirement.

While South Korea’s legal retirement age is 65, companies often push workers to retire early, leaving seniors with many years without significant income.

The study also found that, since women were traditionally the caregivers in the family, an increase of women joining the workforce “weakens the family’s private support of aged parents.”

Since family support for the elderly was traditionally the norm, South Korea only recently developed a pension system, three decades ago. The study found the system inadequate for many Koreans. Those who work outside of big companies are often left without sufficient pensions, since “only workplaces with more than 300 employees have been obligated [since 2019] to introduce retirement pensions.” Furthermore, the public pension system does not account for informal work, leaving people like Jung without a safety net.

“My son helps me,” said Jung, whose adult son lives with her and her husband. Since her son Chi-gu Yoon has no significant income of his own to support his parents, he helps how he can. “I can’t lift heavy things… I couldn’t do this if he didn’t help me.”

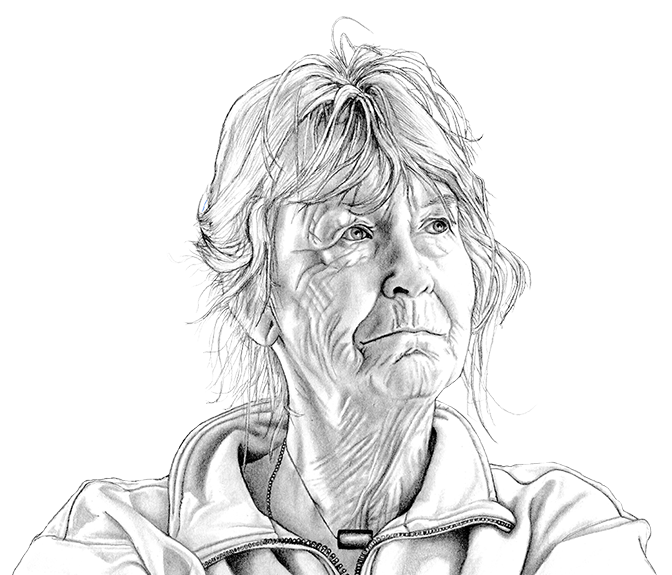

Even some older Koreans, whose children could potentially contribute money to their parents, opt not to turn to them for support, choosing instead to push carts alongside Jung. Yeong-Rye Kim, 76, is a “pyeji sugeo noin” who prides herself on her self-sufficiency. “I don’t want to burden my kids for money, so it’s good that I’m earning my own,” said Kim.

South Korea’s population, 2021 and 2060 projected

South Korea’s population is aging and shrinking. A 2017 study predicted that for South Korean women born in 2030, life expectancy will be among the highest in the world.

Population:

With one of the lowest rates of obesity and smoking, South Koreans today are living longer than ever before – an accomplishment for longevity, but an economic challenge for Korean society.

“You’re expected to live now to 80 or even until 90 years old, but you have to retire at 62, or 63, or 65. Then what do you do?” said Yong Suk Lee, an assistant professor of economics and global affairs at Notre Dame University. “Unless there’s personal savings or if there’s strong government pension support, it’s very likely to fall into poverty.”

“I didn’t go to school,” said Jung. “My maternal grandmother raised me, but she didn’t send me to school because she said women shouldn’t learn to read and write.”

The discrimination many women face in their early years have life-long implications. South Korea has the largest gender gap in median earnings in the OECD. South Korean women over the age of 65 are 30 per cent more likely than their male counterparts to be living below the poverty line.

“The males may have more labour force opportunity to supplement a little bit of income here and there,” said Lee. “Whereas elder females, especially if we think about the elderly right now, who may not be as well educated… they might have to resort more to the informal sector.” He adds that life expectancy for women in South Korea is also higher, which compounds the number of years some older women end up living in poverty.

The work can also pose threats to both physical and mental health. A recent study found that seniors doing this type of work have increased rates of musculoskeletal problems (especially joint pain), depression, and suicide or self-harm ideation, compared to others of the same age.

“My legs hurt, my back hurts, my whole body hurts,” Jung said.

While Lee says “it’s a dire situation” for the elderly of South Korea, key policy changes could make a difference for current and future seniors.

Jung told us she would like to work for the local government office, clearing the roads. The OECD and other expert groups recommend vocational training programs geared towards older adults to help seniors like Jung access safer, more secure and better-compensated work opportunities.

Basic digital literacy training could further expand job options for older adults, as the generational gap in information and communication technology proficiency in South Korea is nearly twice that of the OECD average.

Employment reforms are also needed to improve the financial status of elderly in the future. Raising the de facto retirement age would ensure greater income security for older workers, and support personal saving for retirement.

South Korea’s old-age dependency ratio, 2021 and 2060 projected

According to the OECD, the old-age dependency ratio compares “the number of individuals aged 65 and over per 100 people of working age defined as those at ages 20 to 64.”

In 2021, there were approximately 25 people aged 65 and older for every 100 people aged 20-64.

Source: OECD (Calculated from data accessed Aug 26, 2022), Population projections.

Many employers in South Korea pay workers based on the number of years of service, which can make employing older workers more costly to the company, leading to forced early retirement. The 2022 study on inclusive aging recommended that a transition to role-based compensation – where workers are paid according to their duties – could avoid the cost burden associated with employing older workers, and reduce the need to mandate early retirement.

Experts have suggested various reforms to bolster the pension system, such as shifting to one based on income rather than employment status, and increasing basic allowances, especially for those elderly in severe poverty.

“There are so many different interests at stake in the National Pension system,” says Yoo Hee-Won, a researcher at the South Korean National Pension Service. “Some argue that the pension system should be made more lenient, while others argue that it should ensure financial stability, even if the pension system’s generosity, that is, the level of pay, is lowered.” This absence of consensus and lack of political will has stymied meaningful pension reform.

Until there is the political will, and an effective system, to support seniors like Jung, older Koreans will continue to find ways to make ends meet. As she spoke with us, a man came by with some boxes, “Come here to throw it away,” said Jung. “Now, I have to repack this again,” she said, waving her hand. “Put it in the cart, and go to the junkyard…This is my life.”